This article was originally published in The New Stack on July 22, 2019

For business people, grasping the essence of Kubernetes can be challenging. Most content out there is written for a technical audience and assumes a lot of context non-technical typically people don't have.

So, before we start diving into Kubernetes, let's discuss the basic concepts needed to understand where Kubernetes came from. For technical folks, this may sound very simplistic, and it should. The goal is to offer a simplified overview to understand the big picture. I’ll start with a single computer, move to virtual machines, and then briefly discuss distributed applications. If you’re already familiar with these concepts, feel free to jump to what’s new to you.

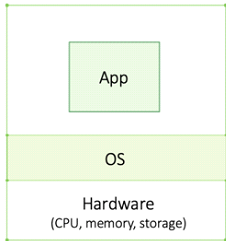

A computer consists of hardware — mainly the central processing unit (CPU), memory and storage — which runs different applications or programs. The operating system (OS) is a software that sits on top of the hardware and manages these resources. Above the OS are the applications (e.g. Outlook or the Microsoft stack on your laptop). The OS schedules when each app has access to which resource ensuring each application has enough to run smoothly (while Outlook and Word may feel like they run simultaneously, they don’t. Believe it or not, your computer cannot multitask. Programs run one at a time. The intervals are so fast, however, that they seem to run simultaneously — that’s OS magic!). The applications are oblivious of the hardware, they only interact with the OS. This principle is called abstraction: a layer that mediates (OS) between two other layers (hardware and apps). Apps don’t need to know anything about the hardware because the OS manages everything.

Before virtualization came along there was no way to isolate applications on the same machine, or server. When dealing with mission-critical applications, companies would typically have one application per server to avoid that, if one application crashes, it would drag another one down with it. Running one app per machine is expensive as each machine has to have the maximum resource capacity the app can possibly reach during its peak, even if it only reaches that capacity one percent of the time — an inefficient use of compute resources. Machines like this (with no virtual machines) are referred to as bare metal.

Co-locating applications optimizes resource utilization. Since it’s unlikely that all application will peak at the same time (you only co-locate apps that aren’t likely to), applications can share peak-time capacity, significantly reducing resource needs. Virtualization enabled exactly that by eliminating the risk of one app crashing and affecting co-located apps.

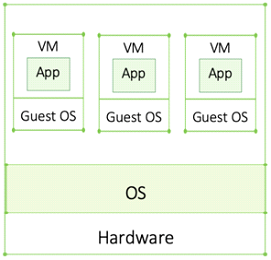

A virtual machine (VM) is code that “wraps around” an application, pretending to be hardware. The code running inside the VM thinks the VM is a separate computer, hence the term “virtual machine.” Just like physical machines, VMs require an OS. An OS running inside a VM is referred to as guest OS, while the OS on the real machine is referred to as host OS.

Isolated with no risk of affecting co-located applications, multiple applications can now run on a single server enabling more efficient resource utilization — a true revolution at the time.

From an application standpoint, there is no difference between running on a VM or a real physical machine. From a system administrator’s perspective, however, VMs are much more convenient since adding or deleting VMs is significantly easier, simplifying day-to-day infrastructure management.

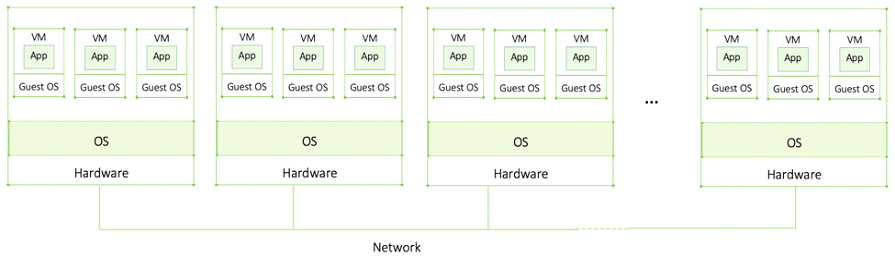

Enterprise applications can be huge and often require way more compute capacity than a single machine can handle. Parallel computing, running multiple programs at the same time, may also be required. In order to achieve that, multiple machines are connected through a network forming a distributed application/system. The two main characteristics of a distributed system are (1) a collection of autonomous virtual or physical machines (2) that appears as one single coherent system to the end-user (which can be a person or an application).

A group of machines that works together forms a cluster; each machine is referred to as a node. For a cluster to realize a common goal, nodes must communicate or “exchange messages.” Over the network, data is exchanged, commands given or accepted, status updates provided, etc.

The key concept here is that a cluster or distributed system becomes one big powerful machine even though the nodes may not necessarily be located in the same physical location.

Unless we are dealing with monolithic applications (typically older applications that were built as one single entity), these large distributed applications are modular and broken down into several components that are placed into VMs. This eases updates, fixes, and rollouts. It also means that if one component crashes, the entire system isn’t necessarily down.

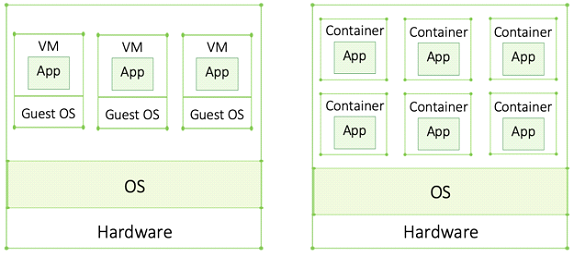

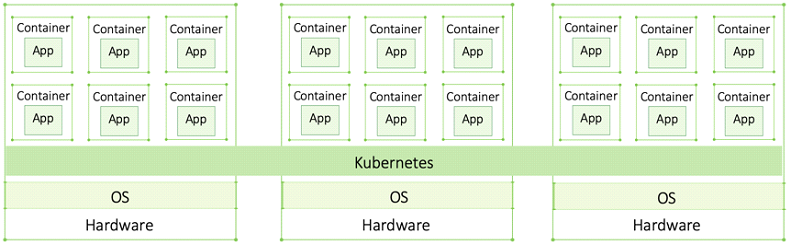

Containers are the next step in the virtualization evolution. Unlike VMs which require a guest OS consuming additional resources, containers are more lightweight. That means you can deploy a lot more containers on a single machine than VMs — again a significant efficiency gain.

Another great benefit of containers is that they are portable. Portability means that they work on and can be moved between any environment (e.g. migrate an application from a data center to the cloud) without affecting the application. Everything the application needs is in the container making it completely environment independent — yet another huge development in IT.

When using VMs, on the other hand, infrastructure dependencies remain. Different clouds or data centers have different virtualization tools. That means I can’t just take a VM that resides on-premise and move it to the Amazon Cloud which uses its own virtualization technology. Moving an application requires placing it into a VM for that particular environment as well as further configuration and testing. This brings additional risk and must be carefully planned and prepared for. All this isn’t necessary if you migrate containers, saving companies a lot of resources.

Microservices are applications broken down into even smaller components. Each microcomponent is called a service — hence microservices. More components mean more VMs or containers are needed. The fact that containers require a lot less resources made microservices feasible for many organizations which is why we are hearing so much about them now.

Placed into a container, each microservice is isolated from one another. Why is this beneficial? Well, the smaller an independent component, the easier to build, test, deploy, debug, and fix. Clearly, it’s much easier to find a bug in a few lines of code than hundreds of them. Since they are isolated, it’s also easier to roll back should a new feature or update prove problematic. But how micro should a microservice be to be considered as such? One way of defining it is code that can be built, tested, and deployed within a week.

If a legacy app with hundreds of VMs migrates to containers, it may now be composed of thousands of containers. As you can imagine, managing them all manually is just impossible. This is where container orchestration tools, like Kubernetes, come in. The orchestrator ensures the right number of containers are up and running and, if necessary, intervenes to fix it. It automates a lot of otherwise very cumbersome manual work which would make it impossible to scale. A container orchestrator spans across the entire cluster and abstracts away the underlying resources (hardware across the cluster such as CPU, memory, and storage).

Originally developed by Google and donated to the open source community in 2014, Kubernetes is one of the hottest open source projects right now. If you’re reading this you likely know it’s huge, but what exactly does it do?

One way of seeing Kubernetes is as some type of data center or cluster OS. As outlined above, a cluster is nothing more than a collection of computers running on-premise, in clouds, physical and/or virtual machines (yes! You can mix and match) which is connected over a network appearing as a single large computer to the user. Cluster resources are managed by Kubernetes, just like your OS manages the resources of your laptop. Developers don’t have to worry about which CPU or memory their apps should use, Kubernetes takes care of that.

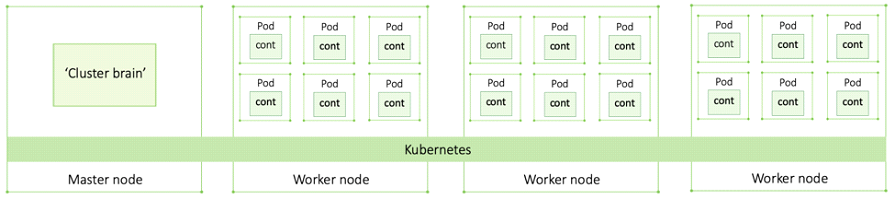

A cluster is made up of a master node and multiple worker nodes. All nodes are Linux hosts (machines running on Linux), although recently Kubernetes started supporting Windows nodes as well. The actual containerized app is running on the worker nodes. Each container is placed in a pod — a sandbox-like environment that doesn’t play a major role except for hosting and grouping containers. To scale an app, you scale pods with their respective containers, not just containers.

The master is the brain of the cluster. This is where all control and scheduling decisions are made. It ensures the application pods are up and running as defined by the declarative state through watch loops (more to that below). No applications run on the master except for system applications. Its function is purely focused on monitoring and managing the cluster.

Kubernetes brings a lot of great capabilities, the most revolutionary are:

Declarative state — at the heart of Kubernetes is the declarative model. Developers declare the desired state of their application (e.g. how many pod replicas with which configuration, etc. their app needs) and Kubernetes implements watch loops to ensure the cluster doesn’t deviate from the desired state. This is a very powerful capability and enables self-healing and scaling.

Self-healing — enabled by the declarative model, Kubernetes ensures the cluster always matches the declarative state. Meaning it heals itself when there is a discrepancy. If Kubernetes detects a deviation, Kubernetes kicks in and fixes it (e.g. if a pod goes down, a new one will be deployed to match the desired state).

Auto-scaling — Kubernetes has the capacity to automatically scale up (spin up more nodes and/or pods) when capacity peaks (e.g. more people watching Netflix on a Friday evening requires a lot more compute resources from Netflix’ servers) and down again after a peak. This is a tremendous asset, especially in the modern cloud, where costs are based on the resources consumed.

Kubernetes is really hard. Expertise is hard to find and it’s not a full-fledged, ready-to-use solution. Kubernetes and containers are only one part of the puzzle. To run applications on Kubernetes in production, enterprises need an entire technology stack. You’ll need something for logging and monitoring (gather and analyze application metrics to know if all is going well), role-based access control, commonly abbreviated as RBAC, (to ensure only those who should get access to a cluster do), disaster recovery, and much more. Configuring and fine-tuning these different technologies so they work well with Kubernetes is no easy task and requires significant resources—time, money, and highly specialized skills. Additionally, Kubernetes’ quarterly release schedule means, companies have to keep up with regular updates. Most organizations have neither the resources nor the in-house expertise to deploy pure open-source Kubernetes.

The complexity of Kubernetes gave birth to numerous Kubernetes solutions. Just visit KubeCon , the official Kubernetes conference, and you’ll see an entire show floor full of Kubernetes solutions — all trying to ease Kubernetes adoption. While some address one particular area (e.g. Portworx, Linkered), others focus on a broader area such as security, compliance, and operations (e.g. Kublr). It can be pretty confusing navigating the space as, at first sight, they are all Kubernetes solutions. However, while the space seems crowded it really isn’t, at least not as much as it may seem.

Breaking applications down into microservices has allowed today’s big cloud-born enterprises (e.g. Amazon, Google, Uber) to rapidly push out new features and updates or roll them back should they not work as planned. This provides them with the agility to adapt quickly, outpacing more traditional competitors. This trend has put enormous pressure on more traditional organizations as their pace of change is significantly slower. The current trend towards digital transformation is driven by the competitive advantage these technologies are providing their adopters. As more companies adopt these technologies, organizations are forced to adopt them too or risk becoming obsolete.

Containers and Kubernetes have revolutionized how companies do business today. Software is playing an ever-increasing role for business success and these technologies are enabling the software to improve and adapt to market demands at an ever-increasing pace. Today, IT is no longer a vertically aligned department; it runs horizontally across the entire organization. Every department is enabled by software, be it a new data analytics tool providing valuable insights about market trends or an AI platform that customizes content to customer needs, increasing retention. Whoever adapts and evolves faster, has a competitive edge.

Since we are at it, let’s put three more related buzzwords into context: cloud native, DevOps, and digital transformation — all part of this trend. The cloud native stack, also referred to as the new stack, is used to build cloud native applications. Cloud native applications are defined as containerized, dynamically orchestrated (a.k.a. Kubernetes), and microservices-oriented. While developed for the cloud, the cloud native stack is not cloud-bound. Today, a lot of enterprises deploy containers and Kubernetes on-premises, sometimes even in air-gapped environments (environments completely isolated from the outside world with no connectivity). In fact, many of Kublr’s users come to us for that particular use case.

DevOps, a methodology enabled by cloud native technologies, integrates development, IT operations, quality assurance, and IT security. Well implemented, it translates into better code, reduced cost as well as a more motivated team. Getting there, however, requires a huge cultural shift within the organization. In fact, experience has shown that it’s easier to adopt the new stack (and that’s quite challenging already!) than changing the corporate culture to embrace this radically different way of doing things.

Digital transformation is the broader term that characterizes this entire trend. It refers to the process of moving an organization to an agile software-first approach to cope with the rapidly changing technology developments — imperative to stay competitive today. Digital transformation is enabled and made more efficient and agile by the new stack and a DevOps approach.

I hope this provided you with the necessary context to read on and learn more about this exciting space. We are currently witnessing a true IT revolution and understanding what’s going on is pretty exciting!